The battle for Baltimore's newspaper

A vampiric villain from afar and a homegrown aristocrat tussle for the future of journalism is Baltimore, and why neither holds the answer for Maryland's working class

Newspapers were originally only for the wealthy. Covering topics exclusively of concern to the affluent, like banking, transportation, and real-estate. And at the steep price of six cents per copy, papers were just too costly for the average early 19th century yeoman.

Then penny newspapers came along. And by reducing the cost of a paper to literally one cent, and reporting on topics of concern to the everyman like crime and labor, news became available to the masses.

It was the novel innovation of selling advertising units next to news, and broadening distribution, that allowed penny papers to prosper despite taking a loss on the sale of each paper. 1

From that day to now, advertising revenue has been the lifeblood of the entire newspaper industry. But since peaking in the late 1990s, those revenues have been progressively collapsing: 2

Take that trend and stack covid on-top of it, and you have what academics are calling an extinction level event for the newspaper. 3

The trajectory of The Baltimore Sun has been no exception.

When The Baltimore Sun was sold to Tribune Company in 2000, joining The Chicago Tribune alongside The Los Angeles Times, industry analysts expected a “monster success”, since Tribune Company, which now had newspapers in multiple major cities, could attract big spending national advertisers. 4

But those advertisers never came. What the analysts did not consider, because they could not foresee, was how the internet would completely disrupt the way that businesses advertise.

So it was for The Sun. Who in 2005, citing a “weak advertising climate”, shutdown two of its five bureaus for foreign news coverage. Less than a year later, the remaining three foreign bureaus were shuddered, as part of an effort to avoid local newsroom layoffs. Local coverage had to come first. 5 6

But local layoffs, if temporarily avoided, would become increasingly inevitable.

During the late 1990s newspaper heyday, The Sun had some 420 newsroom employees. By 2009, squeezed by the great recession, that number shrank down to 140. Now it is said to be as low as 80. 7 8

Alongside a rapidly declining industry, The Sun was reeling.

All the while, laying in wait like a big cat stalking vulnerable prey, was hedge fund Alden Capital. Alden is a uniquely villainous figure for newspapers. Something of a cross between Dracula and Oppenheimer, having been called a “hedge fund vampire” and the “destroyer of newspapers”. 9 10

Perhaps those nicknames are duly given. Alden has a history of acquiring newspapers to reduce workforces and eliminate expenditures, requiring profit margins of 20% in an industry where 10% is closer to the norm. 11

Since Alden took over The Denver Post in 2011, 70% of its workforce has been slashed. One observer separately noted that when Alden came in and took over, pens, notebooks, and even hot water suddenly went missing. 12 13

For Alden’s forty-something-year-old managing director Heath Freeman, such maneuvering is little more than requiring fitness for long term financial sustainability. Nothing destructive or vampiric about it. Businesses exist to produce profit. When revenues get squeezed, cost reductions must follow. Just basic math. Better to downsize and harden today than to liquidate into non-existence tomorrow. And really, all newspapers were shrinking at alarming rates, not just his.

Practical though his mentality may be, as you could imagine, he’s made few friends in the newspaper industry.

But perhaps Freeman sees himself as a sort of tragically heroic figure, like Batman in The Dark Knight, a rogue accepting of being the villain while doing the necessary thing in the long run. Sure his methods are insensitive, but his hedge fund has indeed prevented some newspapers from vanishing all-together. A good thing. Accumulating personal riches in the process is just a bonus. Wealth can be fleeting, but the legacy that would come from being the man to save newspapers in the face of great resistance, much more eternal.

As for the endless vitriol sent his way, it’s nothing compared to the intimately personal trauma he’s already experienced. Like Bruce Wayne, Freeman lost both of his parents too early. That has to change your thinking. Stealing away any idealism. Leaving only a dispassionate acceptance of how the world really works. 14

As Logan Roy recently put it, real life is not a white knight in shining armor saving the day. It’s a number on a sheet of paper. A fight over a knife in the mud. Only when you recognize that can you do the unpopular but essential thing.

If the struggling Tribune Company and its Baltimore Sun were in need of noblesse oblige, they would not find it in Freeman or his Alden Capital. Just cold calculation and a Napoleonic decisiveness.

And so Freeman went in pursuit of Tribune and The Sun. First capturing 25% of the company, buying out dot-com zillionaire Michael Ferro. Then up to 32%. Next he would go for absolute control. And if successful, a thousand cuts would follow. 15 16

This left the entire newspaper industry in despair. Journalism does the public good. To sacrifice that at the altar of profit is wrong. Late stage capitalism hollowing out yet another civic utility. The Sun just won a Pulitzer Prize! Who will hold local government accountable now?

And what of The Sun’s progress in diversifying its newsroom? In the end, would this whole thing be yet another American story of privilege and oppression?

Everything hung in the balance. Alden had to be stopped.

And when The Sun needed a savior most, there was seventy-five-year-old Stewart Bainum.

Bainum grew up in Montgomery County, born into a tight knit family headed up by an entrepreneurial father. Couple that with his being a white male, and Bainum knew he was privileged, later acknowledging that if life were a game of baseball, he started on second base. 17 18

But privilege wouldn’t stop him from learning the value of hard work and empathy. As early as twelve years old, Bainum helped his father with the family hotel business, fixing toilets and helping customers and such. 19

After completing primary school at Takoma Academy in the mid 1960s, Bainum went west for college. Enrolling at Pacific Union, just ninety minutes north of San Francisco and Cal Berkley, an area emerging as the cradle of the anti-vietnam and social justice movements. Perhaps it was here, amidst activism and a revolutionary zeal, that Bainum’s belief in empathy as a bedrock principle was galvanized.

When Bainum returned home he prospered, growing his father’s businesses ten times over and ascending continuously from there. Not only in business but politics too. And eventually even philanthropy, which Burt Cooper would tell Don Draper is the true gateway to power.

So when Bainum saw The Baltimore Sun in the clutches of Freeman's Alden Capital, he knew he had to act. Empathy was at stake, right here in his own community. Because how can folks empathize with people on the other side of town if no one is around to tell their stories?

It was about more than that even. Consider the last five years. Democracy was under threat. It dies in darkness. Journalism brings forth the light.

If Bainum could save The Baltimore Sun by ushering it back into local ownership and operating it as a non-profit, it might set a positive new precedent for how newspapers could operate nationwide. Not for profit, but for good.

So Bainum went to Freeman to negotiate a salvation. Two titans figuratively sitting across from one another, each looking for a read, an opening, an angle. Picture Pacino and De Niro’s diner scene in Heat. Just over Zoom instead of coffee. Completely different ways of looking at the world and the situation before them, but perhaps a mutual recognition and respect of the skill that put them both where they were. Bainum wanted The Sun, and Freeman wanted value, always more value.

As it was, to the shock and delight of many, Freeman agreed to extricate The Sun from Tribune, signing a non-binding term sheet allowing it to be peeled away from its parent company, and sold directly to Bainum, exempting the paper from the ensuing Alden Capital takeover. 20

Relief. Finally The Sun would return to local ownership. And it would be rightfully converted into a non-profit. Jobs would be saved. Stories would be told. Governments would be held accountable. Of empathy there’d be more. Perhaps the death of democracy even staved off.

Sometimes a hero really can save the day. In Baltimore, the light shone through. All that was left was to sort through the details of The Sun’s secession.

But it was in those details that a bedeviling disagreement between Freeman and Bainum emerged.

As it happened over time, being a parent company, Tribune had consolidated a variety of corporate services that were then distributed back out to each child newspaper. Functions like human resources and technology were managed centrally, freeing up local newsrooms to focus more on what they did best, local news, and worry less about back office processes. A common practice for conglomerates.

Per the agreement, The Sun would pay Tribune back for those services for a handful of years until they were able to build out comparable services on their own.

But it might have been that those back office entanglements ran deeper than Bainum originally realized. Separating would be complex and costly. And obviously, Freeman wouldn’t be one to provide a discount.

Whatever the exact sticking point, the disagreement persisted. Negotiations broke down. And the non-binding agreement was terminated. The Sun would not be saved. Alden Capital would indeed take over all of Tribune Company, and all of The Baltimore Sun. 21

And that was that. In the modern story of The Baltimore Sun, it was the villain that prevailed in the end.

Bainum still had more to prove, though. The local business model was still broken. He still thought he could fix it. And he still wanted Baltimore to be ground zero.

You see, since newspapers adopted the business model of the penny paper some two hundred years ago, it is advertisers who have been the real customers, not readers.

And when the internet came along, advertisers discovered that Craigslist and then Facebook and Google delivered a better return on investment than print newspapers did. Digital advertising was cheaper, more effective, and maybe most importantly, more trackable.

In 1874 businessman John Wanamaker was one of the first big retailers to advertise at scale with print newspapers. He famously lamented: “half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, the trouble is, I don’t know which half”. If Wanamaker were advertising digitally today, he wouldn’t have that problem. You can track just about everything. (new privacy regulations notwithstanding, a story for another day)

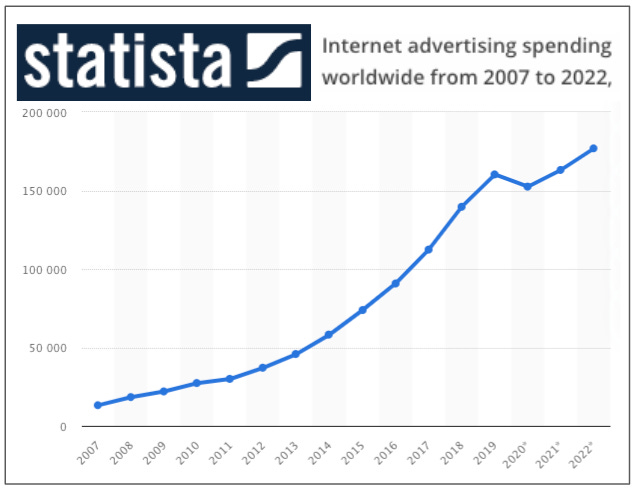

And that is precisely why, as print newspaper ad revenue was collapsing, investments in digital advertising were skyrocketing: 22

Bainum recognizes this. To modernize the newspaper means changing who the customer is. It must be readers, not advertisers, who do the paying.

And as for printing a tangible newspaper, the costs are just too high. Why spend on paper, ink, presses, storage, trucks, fuel, drivers, and shelving when you can pay next to nothing to host a few 1s and 0s on some server in the cloud?

So when Bainum announced he would be starting up his own newspaper in Baltimore, a competitor to the now Alden Capital owned Baltimore Sun, which Bainum would call The Baltimore Banner, he doubled down on reader subscription fees as being the primary driver of revenue for his digital only paper. 23

If newspapers are to last another two hundred years, it will be as digital first B2C enterprises, not physical B2B ones. Bainum aims to validate that concept right here in Baltimore.

But you know, the proliferation of the internet and Big Tech’s consolidation of advertising revenue isn’t the only reason why newspapers have collapsed over the last twenty some odd years. There is another reason. A big one. A reason that none of the newspapers and none of their reporters and none of their publishers want to acknowledge because it exposes them as being partly responsible for their own demise, and an accessory to our increasingly nasty societal divide.

And that reason is this: newspapers are no longer of or for the working class masses.

As Batya Ungar-Sargon argues in her new book, Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy, for most of the 19th and 20th centuries, journalism was a blue collar job. You didn’t need a diploma or a fancy ivy league suit to ask good questions and write down what you observed. You learned on the job, not in a classroom.

Reporters lived right alongside cops, teachers, plumbers, and grocery store managers. They wrote for the common man because they were the common man. Imbued in their reporting were values like family, fairness, honest jobs, low crime, and good schools.

Then something changed. Journalism became a high-status job. Desired by hoighty-toighty intellectuals with liberal arts post-graduate degrees. They came from Columbia and Yale. Their fathers were doctors, executives, and bicoastal money movers.

What caused this sea change?

Maybe it was the TVs that ended up in every post-World-War-II American living room, glamorizing those reporters whose faces talked through the news each night. Ron Burgundy’s legendary vanity is after all rooted in some truth.

Maybe it was Hollywood, who depicted journalism as the most noble cause one could undertake, a crusade in bringing down the bad man, as dramatized in All The President’s Men.

No matter precisely why, it was a new class of ritzy status seeking journalists that came in. But as it still is with a career in news and reporting, high-status aside, the income is still just middling. Most reporters don’t rake in cash, especially not early in their careers, before they’ve had the chance to build a following.

And who can afford to pay lots for education only to make middling money if not the already affluent?

So they became senior reporters, then editors, and they hired more journalists who thought just like they did, and had the exact same backgrounds they had. The same thing happened in academia.

Extrapolate that out over fifty years or so, and the newspaper rank and file are almost exclusively of and for the upper-crust. A one party state in the newsroom.

All of which now results in newspapers no longer representing the interests of the everyman and everywoman, but reporting instead in service of the elitist desire to reorganize society in a way they see as good.

So newspapers increasingly became about race, gender, sexuality, equity, oppression, marginalization, and entitlements. Researchers have proven this by measuring how the usage of these words and others like it have skyrocketed over the last decade and change. 24

And if as a reader, you weren’t on board with all that, it’s because you were deplorable. Deserving of a finger wagged in your face.

And so at this very moment, just as it was at the very beginning, newspapers are again exclusively for the ritzy. Of the affluent niche, for the affluent niche.

That is how you lose the working class. The average Joe and Jane. An audience whose readership and aggregate purchasing power would have been appealing to advertisers who may not have divested their newspaper advertising spend as quickly as they did, had they been able to reach and sell to that consumer base over the last couple decades.

Now to be fair, preserving the working class audience and those advertising to them may not have stopped the collapse of newspapers across the country all together, but it certainly would have slowed it. And maybe, just maybe, kept the likes of Freeman and his Alden Capital at a safe distance to begin with.

As for The Baltimore Sun, you might say it is more Howard County and McDonogh High School with a Masters Degree in Journalism than it is the Eastern Shore with an Associates Degree and on the job learning as an apprentice.

Newspapers here and across the country are at the center of a class divide.

Will Bainum’s soon-to-come Baltimore Banner be any different? Slim chance. It will be new in business model but old in temperament. The same cast of characters with the same backgrounds and the same patterns of thought.

Two of Bainum’s first hires for The Banner came from The Los Angeles Times and The Wall Street Journal. And where might they look for talent to fill out a roster of 50 or so reporters if not The Baltimore Sun? With the evil Alden now at the helm, Sun reporters would probably jump at the chance to come over to The Banner.

And as for ginning up support from those powerful people who can really pull strings and make things happen, there is already speculation that former Democrat presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg will make a sizable donation to The Banner to help it get started. 25

Maybe the Clinton’s, Obama’s, and Biden’s will jump in too, as reciprocation for Bainum having donated millions to their campaigns and other Democratic Party causes over the years. 26

The Sun. Freeman. Alden Capital. Bainum. The Banner. Now Bloomberg etc…

If Game of Thrones taught us anything, it’s that when the high lords play their games of power and influence, the smallfolk often lose out either way. And when it comes to getting common sense local news in service of the everyman, it seems the same is likely to be true here.

And while some existing voices of Maryland’s working class will continue to decry the lack of representation and viewpoint diversity in these establishment papers, whether those papers be hundreds of years old or soon to exist, in my view those efforts will be for naught.

If the question here in Maryland and across the country is how to return newspapers to the working class, the true answer is not to be found in a Bainum newspaper or an Alden Capital one, but rather in the creation of completely new alternatives.

Direct spiritual descendents of the original penny newspapers. Papers that are of the working class, for the working class.

A market that is, once again, anemically underserved.