In May of 2019, Nobel prize winning economist Paul Romer published an article in The New York Times called: A Tax That Could Fix Big Tech. In the article he suggests that Big Tech companies like Facebook and Google are eroding the “norms on which democracy depends” because their targeted-advertising based business models have created a “haven” for “hate speech” and “dangerous misinformation”.

To discourage Facebook and Google from profiting off of such an unsavory business model, and presumably to raise money for state governments, Romer recommends that state legislatures adopt a new “sales tax” on the revenue Big Tech companies generate from displaying ads to residents within a state. [a]

So when a Maryland resident clicks an ad on Facebook, and Facebook makes a couple bucks, the State of Maryland gets a cut.

Well Maryland’s State Senate President Bill Ferguson read Romer’s article in The New York Times and it prompted him to take action. So he partnered with his predecessor, Senate President Emeritus Thomas Miller, and together they set out to tap one of the “untaxed corners of the modern economy” by becoming the first state in the country to levy taxes on digital advertising. [b]

And on January 8th 2020, the bill for Maryland’s digital advertising tax was filed. [c]

If the tax were to become law, the Maryland Department of Legislative Services estimates it would raise $250 million dollars for Maryland in its first year. [d]

Now here is a frank question that seems to have been omitted from the legislative calculus up to this point: does anyone really think that Facebook and Google would actually absorb the costs of this tax straight up?

Of course for Google and Facebook paying out $250 million to the State of Maryland would be little more than inconvenience, but if this legal and financial precedent were to be set, and every state were to adopt similar laws, now real money and entanglements are on the line. And judging just by how much Big Tech spends on lobbying, you can bet they would meet Maryland’s digital ad tax with resistance.

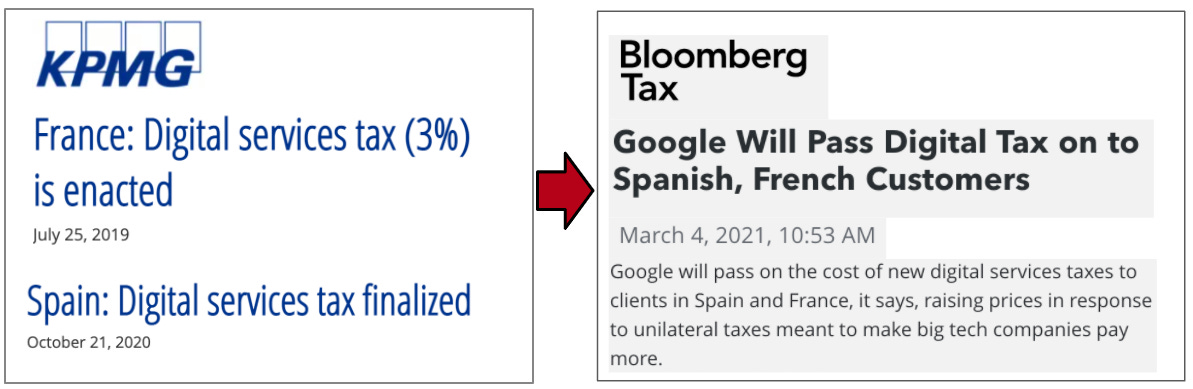

And even if the tax were to become law, still no sweat for Big Tech, they’ll just find a way to pass the costs on down to Maryland’s small businesses and consumers. We know this because we’ve seen them do it before. When France and Spain passed comparable new taxes on digital services in 2019, Google added what it called a “regulatory operating cost” directly to the advertising invoices of Spanish and French businesses. [e]

In fact a 2019 study by Deloitte and Taj on the French digital service tax specifically, found that 95% of the costs from the digital services tax would be accrued by French small businesses and consumers, and merely 5% would end up being accrued by big technology companies. [f]

The Maryland Public Policy Institute recognizes this, and that is why they’ve called Maryland’s digital ad tax just a “tax on small business” that would “unfairly hurt Maryland’s small businesses that rely heavily on digital ads”. [g]

And yes it is generally the small business, not the mega corporation, that relies more heavily on targeted digital ads.

You know there has always been this misconception that the whole of digital advertising amounts to Big Tech selling your personal data to big business so fat cat CEOs can line their pockets by tricking you into buying things. But you know who is really buying your data? It’s the workaday small business owner: the local roofing company that pays a local digital advertising agency to help them advertise to an audience of folks that Google’s algorithm has determined are in the market for a new roof based on their search and browsing history. It really is not sinister or invasive.

If the sinister and invasive use of your personal data is what you seek, more closely fitting those descriptors would be the Big Tech enabled surveillance programs developed by the NSA which were exposed by Edward Snowden and reported on by Glenn Greenwald. When Romer talks about checking Big Techs power to preserve democracy, digital ads need not be the focus of his energies, but rather the Federal intelligence apparatus that discourages dissent by applying the capabilities engineered by Big Tech to monitor the behavior of American citizens en masse. Rufus the advertising roofing company owner will do you no harm, but when it comes to surveillance, we already know that just the threat of being observed is enough to change human behavior significantly. [h]

But to return to the main point: unencumbered digital advertising is good for Maryland’s small businesses.

Most small businesses by nature serve a niche audience, and the precision targeting unlocked by digital allows them to reach those niche audiences in ways previously impossible with TV and print. What’s more, the mainstream adoption of digital made advertising cheaper across all mediums, since it drove up the total supply of available ad units. Per an economist from the Progressive Policy Institute, because of digital, advertising prices “really plunged” which was a “real positive” for both “consumers and advertisers”. [i]

Advertising that is effective and affordable helps small businesses grow. That growth will be hindered if this tax is made law. So you could see why some of Maryland’s advertising leaders spoke out against it.

Writing in The Baltimore Sun, the American Advertising Federation of Baltimore’s President Matt McDermott, said the bill would be a “serious mistake” that will put Maryland businesses at a “competitive disadvantage” since the bill could require Maryland businesses to pay taxes twice: “the digital advertising tax on top of the state income — a double-tax” that out of state competitors would not have to pay. [j]

And it is that notion of a “double-tax” that may draw the scrutiny of the judicial system. According to the dormant Commerce Clause, states are unable to enact taxes that discriminate against interstate commerce, and this state specific tax on transactions over borderless cyberspace may do just that.

Even though costing Maryland’s small businesses money and giving their out of state competition an advantage is plenty damaging enough, the injurious effects of this legislation don’t stop there. Businesses will also have to: read the law, interpret the law, and then comply with the law. All of which is much easier said than done.

When legislative systems that are slow by design enact policies on immutably dynamic industries like digital, the end result usually amounts to vagaries and frustration.

Recall from 2018 the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. GDPR sought to preserve the digital rights of EU citizens with standardized data protection laws, but once enacted was found to be “hopelessly vague” and led to “widespread confusion”. A 2018 report by the International Association of Privacy Professionals found that 56% of companies were “far from” GDPR compliance or would “never comply”. 20% of companies thought compliance was literally “impossible”. [k] [l] [m]

Maybe that explains why the EU Parliament’s own website was found to be in noncompliance with the very regulation it was responsible for enacting. [n]

One year after GDPR, CNBC reported it “created new bureaucracies within corporations” and with those came “tension and confusion”. And despite being maybe impossible, companies spent $7.8 billion trying to comply with GDPR anyway. [o] [p]

Peter Drucker once said the purpose of a business is to create a customer. He didn’t say much about compliance. How many customers might have been created had that $7.8 billion been spent on marketing and innovation?

Despite whatever good intentions about preserving digital rights, GDPR and its ambiguities have amounted plainly to unproductive spending and those pesky privacy policy banners now littering every website known to mankind.

This shows us that: when it comes to understanding and effectively legislating digital, lawmakers have a track record that is less than sterling. And even though Maryland’s digital ads tax is narrower in scope than GDPR, there is little reason to think it would be received differently.

In review of the bill, The Tax Foundation said it is “unworkably vague” and will create “confusion”. Adweek called it a “mess” that is “misguided”. Sean Brescia, who is Principal at Baltimore’s Mission Media, said in The Baltimore Sun that the tax is “vague” and even “dangerous”. He believed the bill's authors must either have “contempt for business” or are “negligently ignorant”. [q] [r]

So just how vague is this thing really? Here is a video of the bill’s author, Maryland’s State Senate President, describing the bill on CNBC:

The components words fail to form a comprehensible whole there. And this isn’t to jeer at the occasional stammer, not at all. The point is that, like GDPR before it, this law is so vague, so ambiguous, that its author, an individual whose profession is fundamentally about communicating with the masses, struggles to convey a meaningful message about it.

To justify the tax being aimed at Facebook and Google, my interpretation of the Senator’s argument is that, because Facebook and Google have benefitted so much from state level investments in things like education and safety, they should have to contribute back financially at the state level: “We’re not seeing the contribution we would traditionally expect from companies who are benefiting from the public investments we’ve made over time, in public education, and in public health, and in public safety.” [s]

But really how much have Facebook and Google benefitted from the State of Maryland’s public investments? If California were making this argument, that would be one thing, but neither Facebook nor Google even have a physical office location in Maryland.

So all things considered, here we have a new state tax that: may be unconstitutional, is poorly conceived, will take money out of the pockets of Maryland’s consumers and businesses, will create burdensome administrative work, bewilders policy wonks, and is generally derided by advertising industry leaders both nationally and locally.

No way this thing becomes law right?

Wrong.

In March of 2020, Maryland’s General Assembly voted it into law. Just weeks later, Governor Hogan vetoed the bill because he thought it would “raise taxes and fees on Marylanders”. But no matter, in the 2021 legislative session, the General Assembly overruled Hogan’s veto and codified the digital ad tax into law anyway, and it goes into effect at the start of next year. [t]

Fees and frustration now loom for Marylanders.

Well as we know the whole point of a tax is to raise revenues for governments so they can then fund what is in the public interest. So what public investment will be made with the revenues from Maryland’s digital ads tax?

As it happened, around the time Romer wrote his think piece in The New York Times, Maryland lawmakers were searching high and low for a way to raise billions of dollars to fund a set of recommended enhancements to the state’s public education system - all without having to raise fees and taxes on Maryland’s residents.

I suppose as long as the fees hitting Marylanders either come from Facebook and Google or in the form of businesses having to raise their prices because their acquisition costs have gone up, the State of Maryland is technically not in breach of their commitment.

As for the public school system, the recommended enhancements came from what is commonly called the Kirwan Commission, a multi-year research project that identified the funding and policy reforms necessary to improve Maryland’s schools. Some of the recommendations include: increasing teacher pay, attracting higher quality teachers, expanding early childhood education, and more funding for at-risk students.

Sounds practical enough at first glance.

But what may not be practical is the cost: implementing the recommendations of the Kirwan Commission will require a $32 billion dollar increase in funding to Maryland’s public schools over a decade. That is, $32 billion in addition to the funding that already makes Maryland’s schools some of the best funded in the country. As of 2018, five Maryland school districts rank in the top 10 nationally in per-student spending. [u] [v]

The State of Maryland is set to cover the majority of the costs, but local governments will need to chip in as well. Baltimore City in particular will be expected to contribute an additional $330 million over the next ten years. That may prove difficult considering Baltimore’s property tax revenue base is thinning: the population of Baltimore recently sank below 600,000 for the first time in a century.[w] [x]

But collectively Maryland’s governments will need to raise billions and billions of dollars. And remember, the digital ads tax, for all its warts, is expected to raise just $250 million in its first year.

Where will the rest of the money come from?

Well hey if the whole idea here is to find mega-organizations that have eroded the norms of democracy to bring in lots of money all the while benefiting from the State of Maryland’s public investments, who better fits that description than the NSA?

After all, the NSA is headquartered squarely in Maryland at Fort Meade. And although the official numbers are classified, it is estimated some 30,00 people are employed there executing against what experts said as of 2013 is at least a $10 billion dollar per year budget. And surely a high number of those employees reside in Maryland and benefit everyday from Maryland’s investments in safety and education. And the whole mass surveillance thing most certainly eroded one very specific norm which democracy depends on: your right to be free of unreasonable searches. [y]

So yeah, maybe the NSA can plug in with some funding for the Kirwan Commission.

No? It doesn’t work like that?

Well then, I guess we’ll just have to keep reading The New York Times until they unveil more new tax ideas.

Sources:

[a] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/06/opinion/tax-facebook-google.html

[c] http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2020RS/bills/sb/sb0002f.pdf

[d] http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2020RS/fnotes/bil_0002/sb0002.pdf

[e] https://blog.salesandorders.com/google-ads-new-surcharges-to-be-billed-in-france-spain

[f] https://taj-strategie.fr/content/uploads/2020/03/dst-impact-assessment-march-2019.pdf

[g] https://www.mdpolicy.org/research/detail/proposed-md-digital-ad-tax-is-a-tax-on-small-businesses

[h] https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/01/the-watchers

[i] https://www.adweek.com/media/marylands-digital-advertising-tax-is-a-mess/

[k] https://www.zdnet.com/article/brave-accuses-google-of-using-vague-privacy-policies-that-breach-gdpr/

[l] https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/opinions/gdpr-confusion-chaos/

[m] https://iapp.org/resources/article/iapp-ey-annual-governance-report-2018/

[o] https://www.cnbc.com/2019/05/04/gdpr-has-frustrated-users-and-regulators.html

[q] https://taxfoundation.org/maryland-digital-advertising-tax-vague/

[t] https://governor.maryland.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Taxes-Fees-Veto.pdf

[y] https://money.cnn.com/2013/06/07/news/economy/nsa-surveillance-cost/index.html